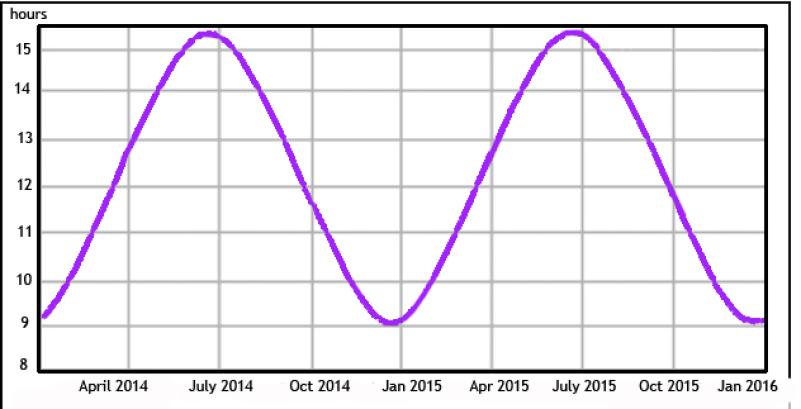

Day length in Northampton in 2014 and 2015. The slope of the line is steepest approximately where it crosses the 12-hour mark (upward in March, downward in September). These points of steepest slope are the equinoxes. Graph adapted from www.oettinger.dk/day-length.

Next Thursday, March 20, is the day known in the northern hemisphere as the vernal equinox, when day and night are approximately equal in length. According to our calendars, this is the day spring begins. (In the southern hemisphere, it is the first day of autumn. Some have suggested the less ambiguous “Northward equinox” for this date and “Southward equinox” for its September equivalent.

These indicate the hemisphere in which day length is increasing.) What is special about this date? There are many answers, astronomical, biological and cultural.

Consider, for example, day length — the time from sunrise to sunset.

Here in western Massachusetts, day length varies from about nine hours on the shortest day in December to about 15 hours on the longest day in June. If you take the day length for each date and make a graph of these for a year (or several years), you will produce a pattern very much like the cross section of a wave on water, a good approximation of the mathematical pattern called a sine wave. Look at how the slope of that curve changes — it goes up most steeply at the vernal equinox in March and down most steeply at the autumnal equinox in September.

If you take the day length for each date and subtract the length of the previous day, you will have 364 differences. The largest of these differences (several minutes per day) are at the vernal equinox in March, indicating rapidly increasing day length, and the autumnal equinox in September, indicating rapidly decreasing day length. The smallest of these differences (less than a minute change from one day to the next) occur at the solstices in December and June.

This rapid increase in daylight, and the approximate equality of day and night, are consequences of Earth’s orbiting the sun with a tilted axis. In June the North Pole tilts toward the sun, in December the North Pole tilts away from the sun, and the vernal equinox is about halfway between the times of most extreme tilt relative to the sun.

Looking at the slope of the day-length graph or taking the difference in day length between successive days are two ways of expressing the same relationship, which gives an answer to what is special about the vernal equinox: that is the day on which day length is increasing most rapidly. A mathematician would express this phenomenon in the language of calculus: on the vernal equinox the first derivative (the rate of change) of day length is at its maximum.

The equinox also has biological significance. Although they don’t use the mathematicians’ formal symbols, many organisms perform some version of the same calculation. For many plants and animals the change in the duration of sunlight is a cue to prepare for the spring and summer. Depending on the species, reproductive organs grow, activity increases, and migration starts or accelerates.

The discoveries that some non-human animals can count and do simple arithmetic have received considerable publicity. In fact, calculus, which is the mathematics of change over time, is more basic to the daily and annual life of living organisms. Not just in keeping track of changing seasons, but also in movement and many internal processes, this “higher” math is integral to life.

Long before a calculus textbook was called “the book that put people on the moon,” birds, bats and insects were performing complex flight, which humans would use calculus to describe.

Just as careful experiments have shown that a few non-human animals can appropriately use abstractions of counting and arithmetic, perhaps similar experiments will some day show that some other species not only move and live with calculus but can also be taught to express some of the language of this powerful tool.

David Spector is a former board president of the Hitchcock Center for the Environment and teaches biology at Central Connecticut State University.

Earth Matters, written by staff and associates of the Hitchcock Center for the Environment at 525 South Pleasant St., Amherst, appears every other week. For more information, call 413-256-6006, or write to us.

Share this page with friends!